Aeolian politics

Under the leadership of President Felipe Calderón (2006-2012), México passed some of the most aggressive clean energy legislation anywhere in the world including legally mandating that 35% of electricity be produced from non-fossil fuel sources by 2024, with 50% of that green electricity expected to come from wind power. For the ancient Greeks, Aeolis was the God of Wind; across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, a 200 km strip of land between the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Ocean, what is called energía eólica—wind energy—has come to occupy lands and sky. Indifferent to the politics and lives of human communities, wind pushes through the Isthmus, a natural wind tunnel owing to the barometric pressure differential between the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Ocean. In the winter months, the north wind routinely blows up to 25 meters/second (55 mph) with exceptional events reaching Tropical Storm force. A study by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory in 2003 confirmed that the Isthmus offers the second best terrestrial resources for wind power development of any place in the world.

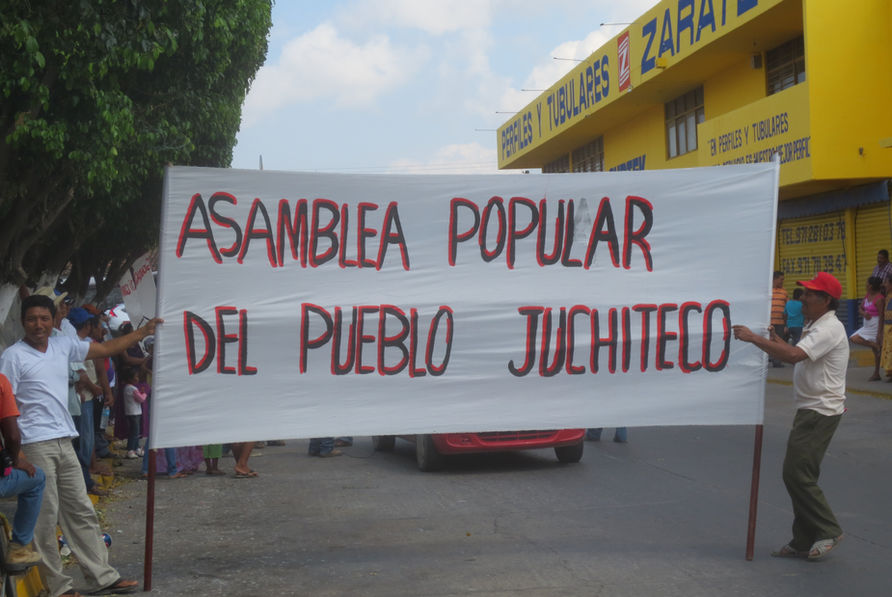

Beginning in 2009 development of those resources intensified in accordance with Calderón’s clean energy plan. In 2008 there were two parks in the core wind zone producing 84.9 megawatts of wind-generated electricity; four years later there were 15 parks producing over 1300 megawatts, a 1467% increase that has made México the second largest wind power producer in Latin America after Brazil. The Istmeño wind boom was the subject of sixteen months of ethnographic field research in 2009, 2011 and 2012-2013 undertaken together with Cymene Howe. We found that the proliferation of wind parks has been contentious at every stage of their installation. Those supporting wind power speak of global climatological good and local economic development. They dream of a “city of knowledge” rising from the ranchland creating a zone of upward mobility where turbine engineering and expertise would flourish in the heart of one of the poorest regions of one of the poorest states in México. Those opposed to wind parks meanwhile see economic imperialism by foreign capitalists coming, once again, to colonize the region through extractive methods that threaten local ecosystems and food sustainability while returning little in the way of general social benefits. Local landowners who receive usufruct rents, caciques (local bosses), and politicians are suspected for taking and issuing bribes to coerce support for wind power projects. Further complicating matters, much of the choicest land for wind development has been held in a centuries-long communal property regime; who is authorized to speak for the comuna has thus become a burning concern that has divided neighbors and families even to the point of violence. Questions about indigenous peoples’ sovereignty and the rights of landless peasants are also constantly in the air.

In local binnizá (Zapotec) and ikojts (Huave) cosmologies, the northern wind has long been considered a sacred power, part of a world-generating life force but also at times dark and destructive, “the devil’s wind.” In the past decade, that northern wind has increasingly become intertwined with land politics, resource politics and the wider biopolitics of life in the Anthropocene. We came to feel that the concept of “wind power,” as it was emerging in Anglo-European neoliberal discourses of modernity, was concealing more than it was revealing of the turbulent forces of wind and power operating in the Isthmus. We started to talk about “aeolian politics” instead in order to deconsolidate the sign of “wind power” and to displace it from familiar technical, moral and economic paradigms of energy decarbonization.

To be clear, both Cymene and I are deeply concerned about climate change and other phenomena of the Anthropocene. We both strongly support renewable, sustainable energy forms. However we have come to question the assumption that wind power, in all its forms and contexts, provides salvation. Modes of wind power that repeat the extractive practices and resource imperialism of the carbon age, we believe, will not be able to tip the scales and intensities of modernization that have led us to the Anthropocene in the first place. Wind power is too often turned toward cleansing the wounds of modernization and its power grids, paying little attention to how it displaces and irritates living beings ranging from some binnizá and ikojts residents of the Isthmus to the mangroves and fish of the Laguna Superior. The lens of aeolian politics reveals that “wind power” turns out to be everywhere a different ensemble of force, matter and desire. This power has no summary form; it is a matter of pressures, flows and frictions, air moving around and through efforts by corporate executives, politicians, engineers, landowners, activists, neighbors and anthropologists to exert their varying degrees of epistemic and moral authority upon it.

If you are interested in reading more, Aeolian Politics culminated in a two-volume duograph, Wind and Power in the Anthropocene (Duke University Press, 2019) whose volumes are available Open Access here and here. We also collaborated with the Ethnographic Terminalia collective to create an Aeolian Politics installation and Wind House at the Emmanuel Gallery in Denver in November 2015.